Let me start this post with a disclaimer – I am a newbie to avalanche terrain and only have level 1 training. I am not a reliable resource for avalanche safety. I decided to write this post anyways because I think a lot of people go out into the backcountry in the winter without understanding the risk. I went snowshoeing and camping for 3 years and told myself I was safe because I “checked the forecast” and only went on popular or “safe” trails. I was pretty conservative, but in retrospect, I didn’t actually know how to read the avalanche bulletins and I was unknowingly venturing into avalanche terrain. Without taking a course, I feel it’s hard to get the proper education on identifying avalanche terrain and my main goal with this post is to convince you to take the AST1 course. If your internal reasoning sounds anything like mine above, trust me, take the course.

Growing up on the East Coast, I 100% didn’t understand the threat that avalanches can pose. I figured they were pretty rare and the odds of me getting caught in one were low. In reality, in 90% of avalanche accidents, the avalanche was triggered by the victim in the accident. So while your odds of getting caught in a naturally triggered avalanche are slim, it’s easier than you think to trigger one. Human triggered avalanches are more commonly triggered by backcountry skiers and boarders rather than snowshoers because of the terrain type, but snowshoers are at risk from other phenomenon’s such as cornices. In addition, avalanche risk is generally at its highest after major snowfalls and that tends to be when lots of people crowd into the backcountry to enjoy fresh powder.

Even if you don’t have avalanche safety training, if you’ve spent any substantial time snowshoeing, you are probably familiar with the avalanche bulletin. The bulletin is a regional mountain forecast issued by Avalanche Canada that tells you the avalanche danger level, problems to look out for, and additional details on the weather and snowpack. Users can also submit reports from their trips on any incidents or avalanche indicators they witnessed, so it’s a useful resource for assessing risk.

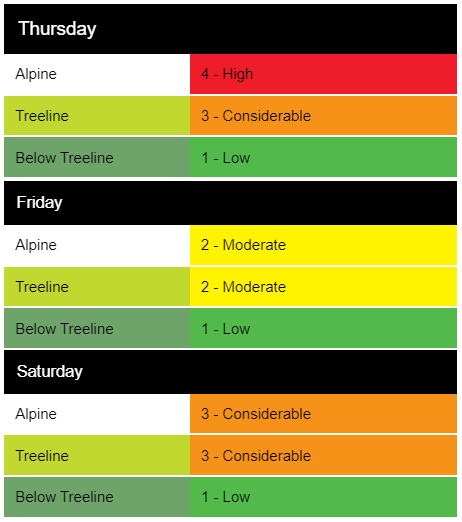

The bulletin has 3 parts that are all equally important, but unfortunately most people (myself included in the past) take one look at the danger rating and never make it past the first section of the bulletin, which contains a 3 day colour-coded rating system. There are 5 levels: low, moderate, considerable, high, and extreme. Level of caution depends on the user. Before I did the training I would comfortably go out in low and moderate conditions, but not considerable. However, I know a lot of users view “considerable” as fine and only stay home in high and extreme circumstances. After doing the training, I wouldn’t venture into avalanche terrain above low unless I had appropriate safety gear.

While it’s great to check the danger rating, the other sections of the report are just as important, particularly the problem areas. These tell you what avalanche risks to look out for, where to look for them, and how catastrophic they might be if encountered. For example, the problem below tells me that the chance of a storm slab avalanche in the treeline and above is actually very likely on all aspects of the slope, but not likely to be larger than a size 2 avalanche. But for the record, a size 2 avalanche is still fairly large and can kill you, so don’t be deceived by the fact that the scale goes up to 4.

Finally, the details section tells me what to expect in terms of weather and snowpack and how accurate the bulletin is. The summary below indicates that heavy rain and snow result in uncertainty around avalanche problems and inclement weather makes the mountains a particularly dangerous place to be at that time. The forecaster indicates further in the report (not shown) that because of significant precipitation, they only had a moderate level of confidence in their predictions, so they should be taken with a grain of salt and other risks could be present.

For me, the avalanche bulletin has become a critical part of my avalanche training and planning because it helps me in making decisions about when to go out or not and what to look for if I do go out. There are lots of ways to mitigate your risk in the backcountry. One is by avoiding avalanche terrain altogether – ie, if I’m not going to go to terrain where there is a risk of avalanche, then I don’t need avalanche safety training. There are some trail maps on Avalanche Canada that indicate the different types of avalanche terrain so that you can avoid challenging or complex terrain. But the bigger problem is that without training, I think it is somewhat challenging to identify what isn’t avalanche terrain. There is often information available on the internet about specific trails, but you are most protected if you’re able to identify avalanche terrain and hazards yourself (although I still highly recommend doing specific trail research as well).

Which brings me to the second part of avalanche awareness – staying safe by avoiding avalanche risks in the backcountry. Most of the terrain I’ve travelled through has been simple terrain, meaning low angle or forested terrain with lower risk of triggering an avalanche (beware though, avalanches can happen in the trees too, so don’t assume you’re safe just because you’re in the forest). However, I did unknowingly travel through some slightly higher risk terrain before getting my AST1. For example, Elfin Lakes and Zoa Peak are two popular winter snowshoe trails – the Elfin trail is all in simple terrain (green), but it does pass under some challenging and complex terrain (blue and black) that could potentially place you in the run-out zone. Likewise, if you go all the way to Zoa Peak, you pass through a section of challenging terrain, but if you just go as far as the sub-peak, you stay in simple terrain. Knowing how to read the terrain and identify potential problems or hazards (all taught in the training), allow you make smart choices when recreating.

For me, these were the two parts of the training that were most eye-opening. Sure, you also learn how to use a beacon, probe, and shovel to conduct a rescue, but so much of the training is about avoiding ever having to rescue someone or be rescued. The more you learn about something you didn’t know very much about, the more you realize how little you actually knew. This was very much the case for me with avalanche training. I was completely blind to so many of the risks that it would have been so much easier for me to walk into a scenario that I didn’t know how to escape from. Now, though I’m still a learner, I can at least acknowledge the magnitude of the information I don’t know.

Finally, the last part of the training is about avalanche rescue. What to do if the worst has happened. You learn to mitigate risk further going around avalanche terrain and by making sure to stagger your party on those occasions when you do have to pass through avalanche terrain so that if there is an avalanche, no more than 1 person will be buried, leaving multiple people to initiate rescue. If you’re not able to be rescued by your companions, it’s very unlikely you will be rescued at all. 91% of people survive if rescued within 18 minutes, after that survival drops to 34% in burials between 19 and 35 minutes.

For this reason, who you recreate with is extremely important because you are potentially relying on your friends to save your life. For this reason, I did my AST1 course with 3 other friends and we practiced together on our snow camping trip last year. I don’t yet own my own beacon and probe (just a shovel), but I have been renting them since I did the training and hope to buy one soon. It’s great if one person in your party has training and can identify hazards and mitigate some of the risk, but unless you all have beacon, probe, and shovel and know how to use it, you will likely be shit out of luck in a real emergency. Fortunately, there are lots of AST1 providers, so I recommend signing up for a course to learn all about avalanche safety and prioritize your safety in winter conditions in the backcountry. I did my course with The Mountain School.

*stats from National Geographic via: https://www.dosomething.org/us/facts/11-facts-about-avalanches#fn3

**since writing I have acquired my own probe and beacon!